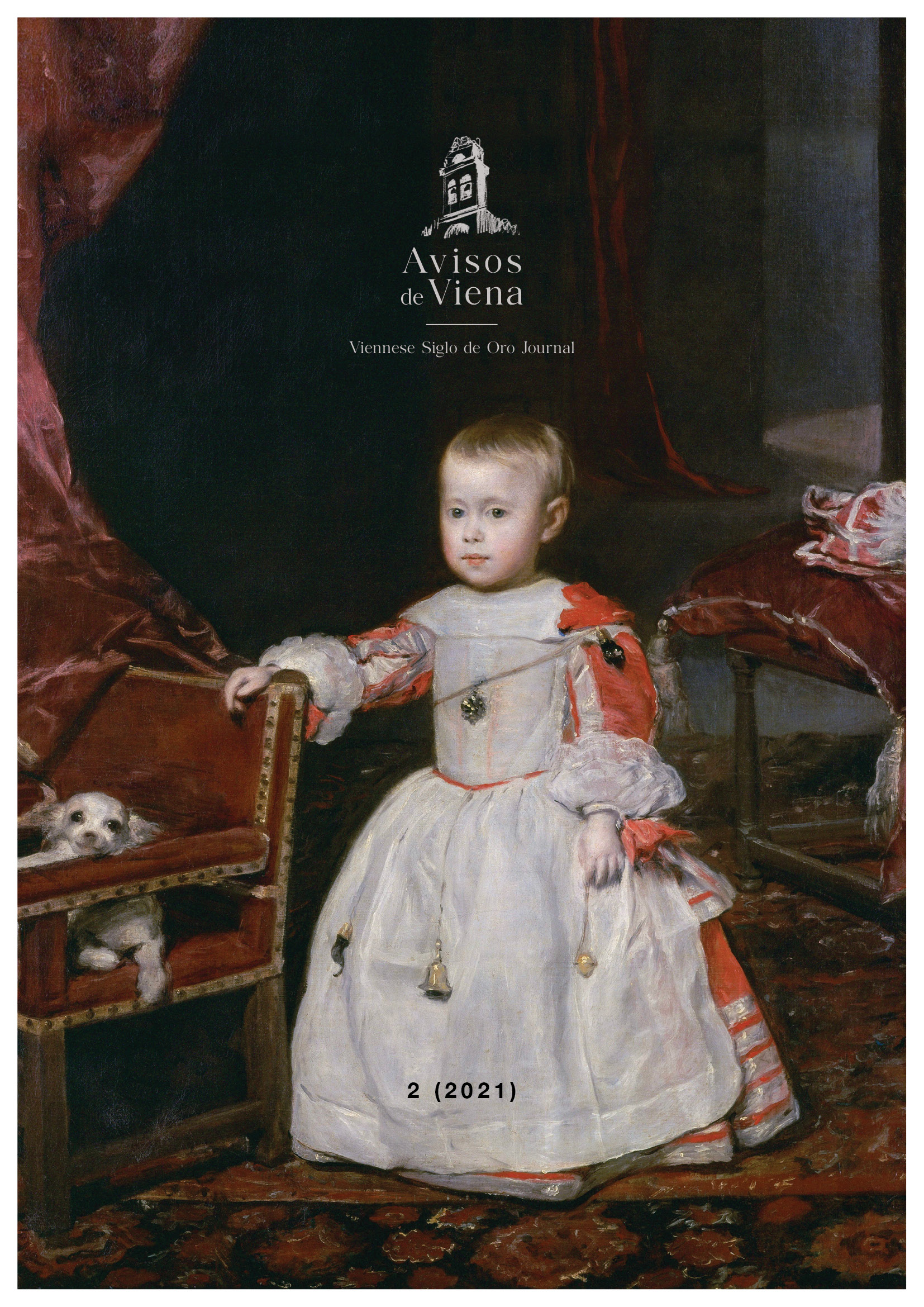

Vol. 2 (2021): Avisos de Viena

Felipe Próspero leaves a strong impression on whoever finds the Spanish room in the remoter realms of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Even more so when visitors contrast the endearing features of the delicate child on Velazquez’s painting with its label which informs them about the noticeably short sojourn of this Spanish prince among the living (28 November 1657 to 1 November 1661). For all its innocent charm, the foreboding sense of death might be part of the composition, depicted with a door and exit opening on the right into an unspecified space.

As we put this Aviso together, birth and early death emerged as a main topic, tackled from different angles: our authors deal with the precarious status of infants in Early Modern Europe, the pressure put on aristocratic women to outweigh the numbers of death through ceaseless fertility, the (often futile) attempts to guarantee health with the best milk fed by the most promising wet-nurses, and the support granted by grandmothers. We deal with outbursts of joy to celebrate birth (in Spain as in the Ottoman Empire) in its sharp contrast with subsequent mourning and the construction of burial monuments for deceased offspring.

Calderón de la Barca was strongly associated with the Casa de Austria and theatre performances at court, which far from indulging in superficial entertainment, time and again refer to intimate family issues. Playwrights seem eager to provide compassion and consolation for a queen like Mariana de Austria, mother of Felipe Próspero: Mariana spent the first 12 years of her marriage in an uninterrupted chain of conceptions, miscarriages, and care for sickly children who were doomed before they were born. She had to endure the death of one child, Felipe Próspero, five days before giving birth to another, the future king Charles II of Spain in November 1661 (our next issue will present unstudied documents concerning this still unexplored side of the queen’s life, and the emotions she expressed about it in her letters.).

Thus, prince Felipe Próspero also makes for a good introduction to Siglo de Oro literature and drama, the second main concern of this publication, with articles on the symbolism of light and darkness on Calderon’s stage, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s vision of the love that binds Eco to Narciso, the metaphor of the viper in Calderón and Lope de Vega, as well as – introducing prose writing – literary imaginations of intrauterine voices, and a rogue’s early childhood traumas.

It is worth remembering that Fernando de Rojas’ masterpiece La Celestina, mother of Spanish Golden Age prose and theatre links gynaecological and surgical issues with the power of rhetoric unfolded by a successful procuress. Each of these aspects is dealt with in a study included in this collection of articles.

We very much hope this issue generates the same interest and kind response as its predecessor.

Wolfram Aichinger